"Adjudication Board"

Adjudication Board

By Simon Tolson, Senior Partner, Fenwick Elliott

Slides from the PowerPoint presentation which accompany this article may be downloaded here [1]

(i) Key characteristics of an effective Adjudicator and (ii) ANB Evaluation Processes from TeCSA view point

Key Characteristics of an effective Adjudicator – attributes and skills

Starting point:

The Technology and Construction Solicitors Association (TeCSA) view has always been that it should set appropriately high standards for those who join its adjudication panel and who therefore may be nominated from time to time to act as Adjudicator. TeCSA keeps these issues under regular review as the law and practice is ever moving.

This is natural and normal as TeCSA has been at the heart of the development of statutory adjudication since even before its introduction with the 1996 Act1. Indeed TeCSA (then ORSA) produced the first set of compliant adjudication rules in 1995.

Once upon a time, when I was not much more than a lad, statutory adjudication was the new kid on the block, when most construction people were confronted with their first adjudication dispute, or were wondering whether to name someone as the adjudicator in a contract, they looked at a list of names they were familiar with from their experiences of arbitration, e.g. the late Harold Crowter, Mark Cato, John Sims, Eric Mouzer etc, and wondered whether those same people would be any good at adjudication. You know what they were! In those early days, the adjudicator-nominating bodies (ANBs) had drawn up lists of names, but a large number of those names were unfamiliar to most people.

Nowadays, with so many “safe hands” around, things are a rather easier for people, especially as the ANB lists are so well established and people undoubtedly have their preferred individuals. Parties are used to naming an adjudicator in their contract or agreeing someone to act as the adjudicator once the notice of adjudication has been served.

Honesty and integrity

Being honest and impartial are a key characteristic of an effective Adjudicator and that attribute applies for as long as an adjudicator holds him or herself out. Of course, we have seen that some adjudicators come unstruck right at the start of the process when they accept appointments.

As we all know, it was not unknown for some referring parties to attempt to manipulate the adjudicator appointment process by presenting spurious reasons why certain individuals should not be appointed. There is no guarantee that the adjudicator nominating body will take any heed of such representations, (although some plainly did) particularly where the explanation offered by the referring party makes no serious attempt to substantiate conflicts, as an ANB cannot exclude adjudicators from being appointed, except where a genuine conflict of interest exists. However, let us be clear, TeCSA never yields to such requests without some enquiry looking at the reasons, and operates a cab rank rota, as many of you know. The cab rank is departed from only where specific expertise or experience is required for the adjudicator, such as with PFI/PPP project finance experience, or say a dispute involving nuclear implicated regulation. TeCSA has for many years maintained a central register of all adjudicator appointments. It knows who has been appointed, when and the parties. For this reason the issues in Eurocom Limited v Siemens Plc2 were not an issue before or since this case lifted the lid off questionable practices that had developed in some appointment processes.

Both Eurocom, a decision of Ramsey J sitting in the Technology and Construction Court and the later decision of Hamblen J, in the Commercial Court in Cofely Limited v Bingham and Knowles Limited3 illustrate the lengths to which some parties will go to steer the nomination process and secure the tribunal of their choice. Some view these practices as innocent forum shopping; others like me see them as deeply unsavoury. What is clear is that these practices had become by no means exceptional or even unusual in some quarters.

Therefore, Hamblen J’s judgment in Cofely Ltd v Bingham and Knowles acts as a reminder to all those involved in our industry of the relationships that may develop and the need for transparency about those relationships. A key characteristic of an effective adjudicator is being honest and not objectively biased4 or apparently in the pocket of a party that refers disputes, even to just appear so is dangerous (for apparent bias reasons5).

Adjudicators should continually bear in mind the need to disclose to the parties any actual and/or apparent conflicts of interest, irrespective of whether they have been appointed by one of the parties or, an appointing institution. In Cofely, the arbitrator’s failure to disclosure the fact that Knowles had been involved (either directly as a party or in its role as representing parties) in appointing him as arbitrator/adjudicator in 25 cases over the course of three years, despite the requirement in his nomination form to disclose ‘any involvement, however remote’ with the parties, contributed to the finding of apparent bias.

I believe that the outcome of these cases has acted as a real deterrent to these practices in the future. TeCSA expects its adjudicators to be fully cognisant of the judicial illumination from the Courts as the courts will not tolerate acts by a referring party, which result in the “pool of possible adjudicators” being “improperly limited”. Neither will it tolerate adjudicators being less than forthcoming on declaring interests.

Adjudicators, like arbitrators, should handle requests for information regarding their relationships with parties in a professional, considered manner, and should refrain from ‘descending into the arena‘. The repeat appointment of adjudicators / arbitrators is a fact of modern practice, which means that full disclosure, for the purposes of doing justice to the parties, is necessary in order to preserve the integrity of the relevant dispute resolution process. TeCSA takes this issue most seriously.

Make no mistake, adjudication in 2017 is a “formal dispute resolution forum with certain basic requirements of fairness” to quote from Fraser J who said in Beumer Group UK Ltd v Vinci Construction UK6 adjudication:

“… for all its time pressures and characteristics concerning enforceability, is still a formal dispute resolution forum with certain basic requirements of fairness…” and “ … although adjudication proceedings are confidential, decisions by adjudicators are enforced by the High Court and there are certain rules and requirements for the conduct of such proceedings. Adjudication is not the Wild West of dispute resolution.”

That also means an adjudicator needs to behave and conduct themselves with transparency and must have a clear rounded understanding of the law in relation to such things as actual and perceived bias. The cases of Eurocom and Cofely show how important transparency is, that it is not just about being transparent, but also about being seen to be transparent. As they say, sunlight is the best disinfectant.

Most recently in Beumer Group we saw a striking example of obfuscation and poor candour by that adjudicator's failure (Dr Chern) to disclose his involvement in a simultaneous adjudication involving one of the parties which was a material breach of the rules of natural justice. After considering the relevant authorities on the matter, Fraser J determined that there was a clear breach of natural justice. By parity of reasoning with Dyson LJ in Amec v Whitefriars7and, more recently, Coulson J in Paice and Springall v MJ Harding Contractors8, he considered that if a unilateral phone call between the adjudicator and one of the parties could lead to the appearance of sufficient unfairness to deny enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision, then there was no scope for arguing the case before him did not also have the appearance of sufficient unfairness:

“If unilateral telephone calls are strongly discouraged (if not verging on prohibited) due to the appearance of potential unfairness, it is very difficult, if not in my judgment impossible, for an adjudicator to be permitted to conduct another adjudication involving one of the same parties at the same time without disclosing that to the other party. Conducting that other adjudication may not only involve telephone conversations, but will undoubtedly involve the receipt of communications including submissions, and may involve a hearing. If all that takes place secretly, in the sense that the other party does not know it is even taking place, then that runs an obvious risk in my judgment of leading the fair minded and informed observer to conclude that there was a real possibility of bias. All of this can be avoided by disclosing the existence of the appointment at the earliest opportunity.”

As to the panel, some truisms:

- Any person may practice as an adjudicator without endorsement in that capacity from any professional body!

- It is not necessary for a person practising as an adjudicator to be on the list maintained by any adjudicator nominating body.

- If someone has a good reputation in the construction industry, or with those who serve the construction industry in dealing with claims, once on the panel and provided they keep a clean nose and the CPD they will receive adjudication appointments irrespective of any third party endorsement and….

- They do not have to be a Solicitor!

- Plainly, some basic legal training and familiarity is essential, but not all adjudicators need to be legally qualified. The person best capable to deal with a dispute will rest on the type and facts of that dispute. An engineer to look at an engineering dispute, an architect to look at design, a quantity surveyor to look at value and quantum and so forth.

With that in mind, TeCSA says of its panel:

The process of adjudication has of course at its heart speed, economy, and some quasi arbitral principles. The adjudicator’s task is to:

- Ascertain the facts and the law;

- Without disproportionate expense, but that still means doing ones best;

- Within the constraints of the 28-day process as may be extended;

- Having regard to the contractual rules and the law;

- Having regard to the provisional and binding nature of the Decision;

- Act fairly and impartially9 as between the parties, giving each party a reasonable opportunity of putting its case and dealing with that of his opponent; and

- Adopt procedures suitable to the circumstances of the particular case, avoiding unnecessary delay or expense, so as to provide a fair means for the resolution of the matters falling to be determined.

A paramount consideration for TeCSA is the high standards of those who join its panel and who therefore may be nominated from time to time. Three principal factors for starting off with a suitable candidate:

(i) by section 108(4) of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996, a construction contract must provide in writing that “the adjudicator is not liable for anything done or omitted in the discharge or purported discharge of his functions as adjudicator unless the act or omission is in bad faith”. This very wide statutory immunity leaves parties very much in the hands of an adjudicator, without effective redress in the event of conduct which is unsatisfactory but which falls short of bad faith. TeCSA therefore considers it extremely important to seek to appoint only adjudicators who demonstrate appropriately high standards of good judgment and competence;

(ii) As the ‘premier’ appointing body from principally within the legal profession10, TeCSA is conscious of the desirability of maintaining its reputation as a body that can be trusted to nominate a high quality adjudicator. This reputation can only be maintained if the reality matches the expectation;

(iii) TeCSA adopts an Overriding Objective:

“The overriding objective of the TeCSA Adjudication Service11 is to promote high quality dispute resolution processes to the construction, engineering and technology industries” [Emphasis added]

The TeCSA requirements and assessment procedure for adjudicators are designed to implement the quality approach explained above and the TeCSA Adjudicator’s Undertaking reproduced as an endnote to this paper underscores this fact[i].

Compulsory CPD for TeCSA Adjudicators and periodic assessments of Adjudicators are part of that qualitative process12.

Given TeCSA offers to the public a service of appointing adjudicators in its ANB role as a nominating body it expects only top adjudicators to apply.

The law lays down some minimum standards of conduct for adjudicators, notably:

(i) The adjudication process should generally comply with the rules of natural justice. This requirement is imposed on adjudicators indirectly, by means of the Court’s power to declare that an adjudicator’s decision is invalid where natural justice has not been adhered to. However, this power is exercised sparingly, and there is copious authority on the desirability of overlooking minor or immaterial breaches; and

(ii) the general law also requires adjudicators to act in good faith.

Beyond this bare minimum, it is left to adjudicator nominating bodies themselves to set their own standards for the persons whom they nominate as adjudicators, which is what TeCSA does, and it keeps this under regular review.

Parties to a dispute are free to agree on the identity of a construction adjudicator if they wish to do so. Some construction contracts name an adjudicator or provide a list of names from which the Referring Party may choose. Many contracts (and especially published standard forms) provide for appointment, if the parties do not agree on a particular adjudicator, by one of the recognised adjudicator nominating bodies.

The default position under the statutory Scheme for Construction Contracts, Part 1, paragraph 2(1)(c), if no more specific provision is made, is that the Referring Party may ask any adjudicator nominating body to select a person to act as adjudicator. “Adjudicator nominating body” (ANB) is defined in paragraph 2(3) of the Scheme: “a body (not being a natural person and not being a party to the dispute) which holds itself out publicly as a body which will select an adjudicator when requested to do so by a referring party.” TeCSA is one such body.

The service TeCSA offers to the public is a service of appointing adjudicators in its role as such an ANB body. The TeCSA requirements and assessment procedure for adjudicators are designed to implement the approach explained above.

Key characteristics of a good adjudicator when deciding whether to accept an appointment

A pivotal moment for an adjudicator is of course when he or she is approached with a nomination. The very first question an adjudicator should ask himself, when deciding whether to accept an appointment, is “Do I have jurisdiction?” In other words, can the adjudication process be set in train at all? Whilst, an in-depth analysis is not necessarily required at this stage, an initial and proportional review to flag any issues should be undertaken by the adjudicator. In order to determine this, an adjudicator should ask himself the key questions listed below.

(1) Is there a conflict of interest preventing me from acting?

(2) Does there appear to be an obvious problem with any of the checklist jurisdiction issues listed below:

- Is there a contract?

- When was the contract entered into?

- Is the contract a construction contract within the definition of sections 104(1) and 105 of the HGCRA?

- Is the contract with a residential occupier and excluded by section 106 of the HGCRA?

- Does it relate to construction operations within the territorial application of the HGCRA?

- If the contract is not a construction contract under the HGCRA, does the contract expressly provide a right of adjudication in any event?

- Has the adjudicator’s appointment been made in accordance with the contract? Has the referral been validly made?

- Is there a crystallised dispute?

- Has the dispute arisen under the contract?

- Has more than one dispute been referred to the adjudicator? If not how closely related?

- Has there been a previous adjudication on the same dispute?

- Are the parties to the contract the same parties who are bringing the adjudication?

The adjudicator will have limited information at the very outset, but all of the key questions should be kept under review until any further information becomes available. The adjudicator should consider whether requesting further information from the parties might assist in resolving some of these key questions, and this can be balanced against the fact that the parties might by their conduct just submit to the adjudication process.

It is seldom going to be possible for an adjudicator to reach a conclusive view on this when deciding whether to take an appointment. This is because all the adjudicator is likely to have to look at is the notice of adjudication. The notice is likely to allow the adjudicator to answer the first question posed, “Is there a conflict of interest preventing the adjudicator from acting?”, but it is questionable whether it will contain sufficient information to enable the adjudicator to decisively answer the remaining questions such as, whether there is a contract, whether a dispute had crystallised, or whether there is more than one dispute. This might be why the Adjudication Society and Chartered Institute of Arbitrators guidance note has been updated to clarify that an in-depth analysis is not necessarily required, and that “an initial and proportional review to flag any issues should be undertaken”.

Anyhow, once an adjudicator has satisfied himself with the answers to these questions, there are two further questions that are worth asking, as a matter of good practice, before the adjudication process commences.

These are:

- Is the dispute too complex to be fairly determined within 28 days?

- Do I have the necessary expertise?

- Further, if there has been a previous adjudication, an adjudicator should also consider whether he has been asked to decide a matter on which there is already a binding decision by another adjudicator.

In addition, the adjudicator might wish to consider two further questions:

- To what extent is there jurisdiction to deal with the costs of the adjudication; and

- The jurisdiction to deal with slips, errors and mistakes in the decision.

The LDEDCA clarified the law in respect of these two areas. First, in respect of costs, the contract cannot state that one party will bear the costs of the adjudication prior to the notice of adjudication being issued unless the contract also confers power on the adjudicator to apportion his fees and expenses between the parties. Any agreement in respect of apportionment of the parties’ cost reached after service of the notice must be in writing. The power of the adjudicator under LDEDCA to apportion his fees remains unchanged.

Mr Justice Jackson (as he then was) had the following to say in Carillion Construction v Devonport Royal Dockyard Ltd [2006] BLR 15, CA. on the issue of jurisdiction:

- The adjudication procedure does not involve the final determination of anybody’s rights (unless all the parties so wish);

- The Court of Appeal has repeatedly emphasised that adjudicators’ decisions must be enforced, even if they result from errors of procedure, fact or law;

- Where an adjudicator has acted in excess of his jurisdiction or in serious breach of the rules of natural justice, the court will not enforce his decision;

- Judges must be astute to examine technical defences with a degree of scepticism consonant with the policy of the 1996 Act. Errors of law, fact or procedure by an adjudicator must be examined critically before the Court accepts that such errors constitute excess of jurisdiction or serious breaches of the rules of natural justice;

- Jurisdiction for the purposes of adjudication can be divided into two “stages”. The first of these is threshold jurisdiction, that is, can an adjudication be set in train at all? There are strict criteria which must be complied with in order to achieve threshold jurisdiction. Once the adjudicator has determined that he does have jurisdiction then care must be taken not to lose it or, once again, his decision will not be enforced. The adjudicator should always ask himself of what dispute is the Adjudicator seized?13 Care needs to be taken to see that the applicable rules or procedure for the adjudication are identified, which might be set out or referred to in the contract or, by implication, the statutory Scheme.

The purpose of this Guideline is to provide practical guidance to adjudicators on:

- Examining whether they have jurisdiction to determine the dispute at the outset (i.e. threshold jurisdiction);

- Remaining within their jurisdiction;

- How the parties to an adjudication can challenge an adjudicator’s jurisdiction;

- An adjudicator’s power to decide whether he has jurisdiction; and

- Dealing with jurisdictional challenges.

Please note that this Guideline is not intended to provide chapter and verse on the law regarding these matters which is, in any event, subject to change. Any adjudicator who, as a result of this Guideline, has doubts as to his jurisdiction should consult the HGCRA as amended by the LDEDCA (or the old un-amended HGCRA as applicable), together with the relevant case law and any relevant commentary. TeCSA expects no less of its adjudicators.

Key characteristics on the job

Top ANBs like TeCSA expect adjudicators to have sufficient knowledge of the Acts and the relevant Statutory Instruments14 comprising the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the 1998 Scheme’ applicable to contracts under the 1996 Act or ‘the 2011 Scheme’ applicable to contracts entered into after 1 October 2011) (and together ‘the Schemes’) together with an understanding of the court’s interpretation of them at the time.

Adjudicators are expected to be aware of how the drafters of the standard form contracts have incorporated the requirements of the Acts into their documents and, where a particular standard form of contract forms the basis of the construction contract out of which the adjudication arises, grasp how that contract works and has been construed by the courts. Knowledge of the various procedural rules that apply under certain contracts will also be desirable.

Adjudicators are expected to have a detailed, accurate and conversant understanding of the current practice and procedure of adjudication and to have a sufficient knowledge of the general subject matter of the dispute to be able to identify the relevance of all matters before them. Above all else, adjudicators are expected to be available, and be prepared to carry out the function of adjudicator within the timescale allowed. This is a very important fact to note because it is almost certain that it will not be known at the time of nomination if the timescale will be extended, however complicated the dispute.

By assenting to be nominated or appointed by TeCSA, TeCSA adjudicators are in effect holding themselves out to be competent to and able to deal with the specific matter referred within the period allowed for the adjudicator to reach a decision. TeCSA demands the highest standards from those on its panel of adjudicators. Complaints relating to the conduct of TeCSA nominated or appointed adjudicators are investigated thoroughly. Any complaint that is upheld may result in a disciplinary action being taken by TeCSA15, which may include the adjudicator being removed from the TeCSA panel of adjudicators. Something we have only done twice in over 20 years.

The characteristics of a “high quality” service means TeCSA as an ANB sees itself as making:

- enforceable Adjudicator appointments

- with minimum fuss (and expense) and one that nominates…

- high quality Adjudicators, “fit for purpose” who uphold the highest standards.

What makes a good adjudicator? What are their characteristics? Are they different from those that make good arbitrators, or even good Judges? Is one adjudicator better than another? The four following characteristics seem to be essential, and they should come as no surprise to this audience:

- a sound knowledge of construction contracts, standard forms and their payment and valuation processes;

- the ability to manage time, both the adjudicator’s own and management of the parties and the process. An adjudicator needs to be able to plan in detail the course of the adjudication from the outset, so as to ensure that the decision is completed on time;

- an ability not to be distracted by the minutiae so that disproportionate time is spent on red herrings, rates and mice; by peripheral matters;

- an aptitude for writing clear directions and active case management;

- the ability to grasp the essential issues quickly and, therefore, to focus attention firmly on those issues;

- someone who reads the documents, recognises real issues may not be quite what has been expressed and undertakes a proper analysis, focused on the issues, achieves good understanding on the technical aspects relevant to the issue;

- has an open mind, proactive, enthusiastic (not a laggard) and flair never go amiss;

- the ability to treat the parties fairly and politely, no matter what the provocation might be, and wherever possible, to take on board the submissions made by each side, even if the suspicion might be that the documents are not adding to the adjudicator’s understanding of the issues between the parties;

- for the last week or so of the 28 or 42 days, the adjudicator’s own timetable should create the discipline to identify times by which important parts of the decision must be completed;

- as for the decision it needs to be enforceable, soundly reasoned, presented logically and firmly grounded in fact and law. See below.

There are also characteristics that are not always helpful to a good adjudicator. The desire to work out an answer to each sub-issue and in detail is much more of a hindrance than a help. In addition, a detailed specialist understanding of the underlying issues can sometimes cause problems in getting bogged down on secondary issues. Adjudicators are asked to decide points because of their decision-making qualities and their general familiarity with the technical background and relevant law. If the adjudicator has a very specific knowledge of the technical point or legal point in issue then he or she needs to try even harder to ensure that his or her decision is based on the evidence, and not their own technical knowledge or even prejudice as to a parties reasoning and argument.

At a meeting of Society of Construction Law on 11 May 2010, Coulson J as he then was identified what were referred to as the “seven golden rules for adjudicators”. It is worth sharing them here. They were:

(1) Be bold: Adjudicators have a unique jurisdiction16, where the need to have the right answer has been subordinated to the need to have an answer quickly17. Coulson reminds us that the adjudicator's decision can be incorrect (in terms of fact and law) and still be upheld. The important thing is that payment is made to the correct person. Adjudicators must remember that adjudication is all about ensuring that, where appropriate, payment gets to the right people at the right time.

(2) Address Jurisdiction issues early and clearly: Adjudicators should always deal expressly with any jurisdictional challenge, and they should not abdicate the responsibility for providing an answer, even if it is not binding. They should consider the challenge applying common sense, but must avoid being too jaundiced. There will be occasions (however late) when the jurisdictional challenge is made out, and in those circumstances, the adjudicator is going to save everybody a lot of time, money and effort by resigning then and there18. The adjudicator should not shy from dealing with challenges relating to his jurisdiction. Better to exercise caution and withdraw at an early stage than have the decision overturned19. Under the TeCSA Rule 12, the adjudicator can of course decide his or her jurisdiction20. Ensuring an adjudicator has the jurisdiction to decide the dispute referred to him is of utmost importance to the adjudication process.

(3) Identify and answer the critical issues(s): Adjudicators must ignore, unless it is unavoidable, the sub-issues and the red herrings. They should avoid being long-winded and instead concentrate on what they know to be the real point. Everything else will usually fall into place. The adjudicator should make sure he identifies the issues in dispute and deals with each one giving only concise reasons for his decision.

(4) Be fair: Wherever possible, the adjudicator should properly consider every aspect of the parties’ submissions. If the adjudicator has planned out a timetable from the outset then the parties will know what they need to do and when, and disputes over (for instance) the admissibility of last-minute submissions will be much less frequent. The adjudicator should ensure that his decision is clear and free from ambiguities.

Part of fairness is to show no bias. The test, which an adjudicator is required to apply when deciding whether the adjudicator should recuse himself for bias was stated by Lord Hope in Porter v Magill [2002]21 at paragraph 103: “The question is whether the fair minded and informed observer, having considered the facts, would conclude that there was a real possibility that the tribunal was biased”.

In determination of their rights and liabilities, civil or criminal, everyone is entitled to a fair hearing by an impartial tribunal. That right, guaranteed by the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, is properly described as fundamental. The reason is obvious. All legal arbiters are bound to apply the law as they understand it to the facts of individual cases as they find them. The Adjudicator must always remain independent of the Parties. Helping the unrepresented Party may easily create the impression of bias. The limit of assistance is in the matter of not allowing one party to take advantage of the weaker party. Do not make a case for an unrepresented party. Safeguard the party from unfair advantage only.

They must do so without fear or favour, affections or ill-will, that is, without partiality or prejudice. Justice is portrayed as blind not because she ignores the facts and circumstances of individual cases but because she shuts her eyes to all considerations extraneous to the particular case.

(5) Provide a clear result: Most decisions are lengthy and detailed. The adjudicator must always try and ensure that, at the end, they make plain precisely what each party must do as a consequence of the decision.

(6) Do it on time: The adjudicator must complete the decision within the statutory period or any agreed extended period. They must not allow the timetable to slip. It is counter-productive to expand an adjudication from six weeks to three months, because it means that the parties have to spend a fortune, which they probably cannot recover, for a decision that either of them could challenge subsequently. And when the adjudicator has completed the decision, it should be issued immediately. It ruins everything if, as happened in one recent case, the adjudicator completes the decision just as the time was expiring, and then sits on it for three days before deciding to send it out to the parties.

(7) Finally, the adjudicator should avoid making silly mistakes such as arithmetical errors, name and number transposition, awarding interest incorrectly etc22.

It is hard to disagree with the rules Coulson J identified. The adjudication process is generally a quick one. In the early days, adjudication was described as quick and dirty, but temporary23. It is not as dirty as it may once have been24 and often not in reality temporary so the essentials must focus on that expedition aspect and qualitatively it must be up there but bearing in mind it is still essentially a 28 to 42 day process. Note Coulson J rightly cautions against adjudicators getting too bogged down in technical details, especially when the issues fall within that adjudicator’s area of specialism. Do not become a forensic scientist or a mediator (absent express agreement).

In his book, Coulson on Construction Adjudication Coulson J also identifies three characteristics, which he describes as essential for an adjudicator. (He does not address the question of whether these skills are different to the skills that make a good arbitrator.) These are the ability to:

- Manage time (the adjudicator’s own time and that of the parties);

- Grasp the essential issues quickly and focus on those issues;

- Treat the parties fairly and courteously, and to take on board their submissions.

He also talks about the seven golden rules for adjudicators referred to above, which build upon these essential skills.

(ii) ANB evaluation processes from TeCSA viewpoint

In terms evaluation processes TeCSA seeks to ensure its panel meet at least the ethical and professional standards which adjudicators must apply as a matter of general law – it is clear that they, as with any other kind of tribunal tasked with deciding a dispute between two or more parties, are bound to act impartially and according to the rules of natural justice.

As far as the written codified law, s108 of the Act provides:

- 108(2)(e) – duty on the adjudicator act impartially25;

- 108(4) grants the adjudicator immunity from suit but with the proviso so long as his act[s] or omission[s] are not in bad faith.

The Scheme: mirrors the Act.

- Para 12 – a duty to act impartially in accordance with any relevant terms of the contract and shall reach his decision in accordance with the applicable law in relation to the contract...

- Other duties: Para 12 – avoid incurring unnecessary expense.

- Para 13 – may take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law – used sparingly so that such acts do not become a weapon for challenge under the guise of lack of neutrality.

- Para 18 – duty of confidentiality.

- Para 26 – immunity for suit and again as long as the Adjudicator is not acting in bad faith.

The Act and Scheme do not mention independence... if reinforcement is required; it has been supplied through the case law.

TeCSA’s involvement in adjudication is aimed at promoting best practice in all forms of disputes resolution. This is reflected in its approach to evaluation and assessment of its adjudicators. The topic I come to now.

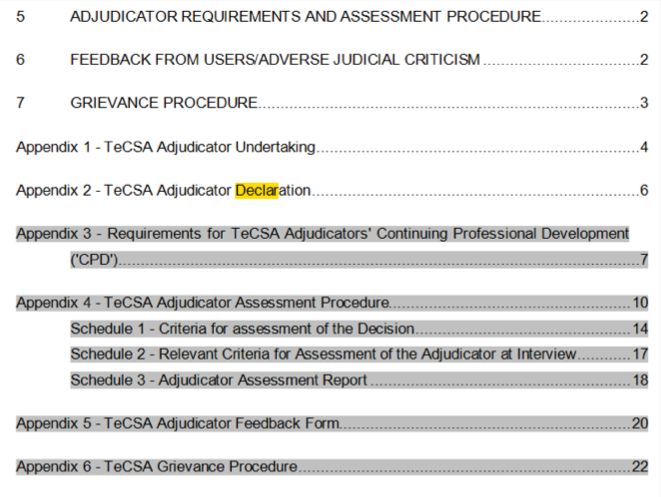

In the current Adjudication Service clauses, 5 and 6 are pertinent as are its related appendices:

Being on the TeCSA list/panel carries with it a duty to do various things are reflected in the Adjudicator Undertaking. This in turn steps down into how TeCSA view each of the panel apropos reaching and maintaining standards at appointment, at interlocutory stages and in production and writing of their decision.

Clause 5 of the Adjudication Service states of the

ADJUDICATOR REQUIREMENTS AND ASSESSMENT PROCEDURE:

Each adjudicator on the Adjudicator List shall:

(a) Give the undertaking in the form attached at Appendix 1 (as amended from time to time) (“the TeCSA Adjudicator Undertaking”);

(b) Undertake the Continuing Professional Development required by TeCSA from time to time. TeCSA’s current requirements are set out in Appendix 2 attached (“the Requirements for TeCSA Adjudicators’ Continuing Professional Development”);

(c) Be regularly and independently assessed in accordance with the requirements of TeCSA from time to time. TeCSA’s current requirements are set out in Appendix 3 attached (“the TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Requirements”).” [Emphasis added]

The Adjudicator Undertaking I have shared with as an endnote, but let us look at what it requires, there is an absolute obligation to:

- Ensure the adjudicator maintains the necessary and appropriate professional indemnity insurance cover adjudication work;

- He or she must respond in good time to the Chairman when offered appointments. The Chairman may offer the appointment to another person without contacting the adjudicator. The adjudicator recognises the need to perform any duties in relation to disputes within appropriate timescales;

- Have appropriate methods of email communication available for all communication with TeCSA;

- Conduct the Adjudication in accordance with whatever rules are applicable under the relevant contract;

- Promptly provide any feedback in relation to an adjudication case history at the request of the Chairman;

- Comply with TeCSA's Adjudication Assessment Procedure from time to time notified to me;

- Keep TeCSA informed about any changes to sectoral areas of his or her skills/work for future appointments and keep ones CV up to date;

- Disclose any conflict of interest in relation to any proposed appointment and also disclose any matter affecting any special requirement indicated in details provided by TeCSA, details of any other past or existing appointments, or issues that he or she may know that may arise during any appointment or in the future, which might have an impact on the appointment;

- Ensure that daily fees shall not exceed the rate of £1,750 (soon to be increased to £2,500) plus expenses and VAT and shall not require any advance payment of or security for fees;

- Recognises he or she have a duty to uphold the appropriate professional and personal standards appropriate to enable the Chairman from time to time to have confidence in making appointments;

- Has a duty to notify TeCSA of any occasion where they have been the subject of judicial comments/criticism and undertake to co-operate with any complaints procedures TeCSA puts in place from time to time.

FEEDBACK FROM USERS/ADVERSE JUDICIAL CRITICISM

6.1 The Chairman will routinely invite feedback from parties by way of a questionnaire. The Chairman may investigate any adverse feedback received (whether in response to any questionnaire or otherwise), and/or any adverse judicial criticism made and known to TeCSA, concerning any adjudicator.

6.2 The Chairman will provide any feedback received and/or any adverse judicial criticism made about an adjudicator to the Assessors appointed in accordance with the TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Procedure.

6.3 Following his investigation the Chairman may in his absolute discretion decide that any adverse feedback and/or adverse judicial criticism concerning any adjudicator gives sufficient grounds to institute an Ad Hoc Assessment under the TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Procedure.

6.4 Any Adjudicator who is the subject of any adverse criticism shall be given an opportunity to comment on the information provided to the Assessors appointed in accordance with the TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Procedure.

TeCSA does reflect carefully on adverse judicial feedback and the TeCSA Adjudication Sub-Committee will meet to discuss individual cases and on occasion there may be cause for the Chairman to call in an Adjudicator for an ad hoc assessment.

If that occurs one thing TeCSA appreciates is that there is always more fact to look at than the judgment and adverse judicial comment in the case of a call in. The Adjudicator is of course given an opportunity to comment on the information provided to the Assessors appointed in accordance with the TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Procedure should an ad hoc assessment ensue.

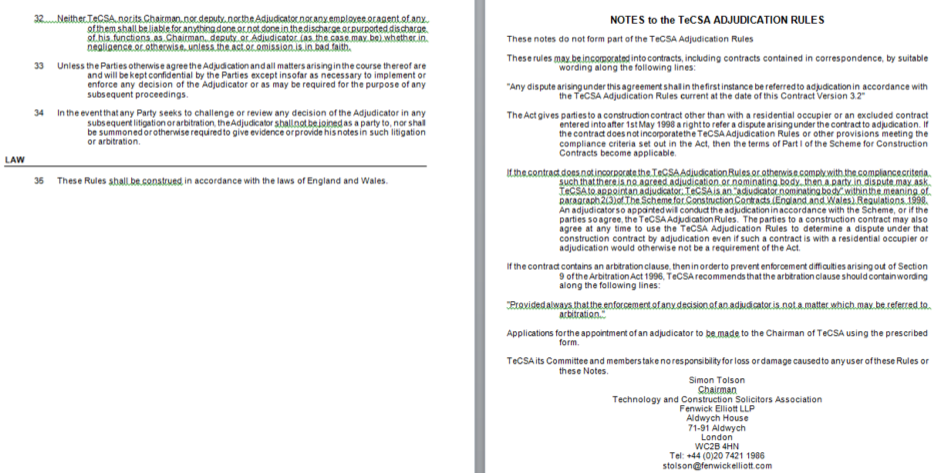

The appeals process in section 7 of the TeCSA Adjudication Service must be understood in its statutory and practical context.

Criteria for assessment of the Decisions

The Act does not provide that the contract should contain any requirements as to the form of decision or any formalities. Neither is there any provision in the Act that the contract must require the adjudicator to give reasons. The Scheme contains no such requirements. In practice, adjudicators often adopt a form similar to an arbitration award but giving shorter reasons for the decision. The TeCSA Rules[ii] do of course assist with the legal robustness of adjudicators decisions by conferring the express power to decide their own jurisdiction. TeCSA recognise:

The style and presentation of a written decision will vary between adjudicators, but certain information should always be included unless compelling reasons dictate otherwise. The Decisions are reviewed by the TeCSA Assessors under three headings, as follows:

Content

(a) The content of the decision will be dictated by, amongst other things, the type, complexity and number of the issues, the extent and nature of the evidence and the personal style of the adjudicator;

(b) The reiteration of evidence and the arguments of the parties should be limited to the extent that is necessary to enable the parties and any third party such as a judge, to understand how the adjudicator reached his conclusions. The parties are already aware of each other's submissions;

(c) There should be sufficient commentary to indicate to the parties and any independent third party how the adjudicator has reached the decision. The reiteration of party submissions on a "cut and paste" process alone does not constitute reasons without further explanation;26

(d) Whatever is written should be set down in an orderly and logical sequence. If there is more than one issue or group of issues the evidence and argument relating to each and the conclusion reached should be separately identified;

(e) Conclusions reached in the body of the decision may in fact be the adjudicator's decisions on the various issues but these should be collected and reiterated where appropriate. It can be confusing for decisions on the various issues to be scattered throughout the decision;

(f) Any requirement for either party to do something should be accompanied by a timescale;

(g) Sums of money are generally exclusive of VAT and this must be stated and explained if appropriate. Interest should be dealt with, if it has been raised by either party. The adjudicator's fees and expenses must be allocated, bearing in mind anything set down in the relevant adjudication procedure or rules. The matter of the parties' costs must also be addressed, if it has been raised by either party. The decision must be signed and dated.

In summary, the content of the decision should generally and ideally include/or refer to:

Introduction

(a) The parties' details;

(b) Representatives of the parties;

(c) Contract and Contract Conditions;

(d) Contract adjudication procedure or Scheme;

(e) Date of Notice of Adjudication;

(f) Method of nomination/appointment and date of acceptance by the adjudicator;

(g) Issues referred and redress sought;

(h) Date of Referral; and

(i) Date for Decision

Jurisdiction

(a) Details of any challenge to jurisdiction;

(b) Response from the other party; and

(c) Adjudicator's conclusion on jurisdiction.

The Adjudication Process

(a) Dates of Response and any Reply;

(b) Date of any meeting;

(c) Details of any information obtained through direct contact with either party or a third party;

(d) Details of any extension of time for making the Decision; and

(e) Details of any particular procedural problems.

Decision

(a) Decision on all matters referred;

(b) Set out the issues logically;

(c) Apply the evidence to determine findings of fact;

(d) Apply the law to the facts;

The assessment procedure - generally five yearly interviews in TeCSA’s Adjudicator Assessment Procedure

Introduction

Six years ago TeCSA introduced an assessment procedure for adjudicators, commencing in 2011. The assessment will include the review of two (redacted) reasoned decisions and accompanying procedural directions made by the adjudicator and also an interview, as described below.

The procedure

The goal of the assessment procedure is to maintain the high standards expected of TeCSA as an Adjudicator Nominating Body ("ANB") in regard to:

- the conduct of adjudications; and

- written decisions.

Save in the case of an Ad Hoc Assessment (see section 3 below), generally all adjudicators on the Adjudicator List will be assessed once every five years by rotation. The names of those to be assessed in each year will be selected by the Chairman in his absolute discretion.

The assessments will be carried out by two TeCSA Committee assessors being members of the Adjudication Review Panel.

The appointment of the Assessors

TeCSA will write to each adjudicator to be assessed in the relevant year at the same time as the CPD annual return forms are requested, usually in September. The names of the proposed Assessors will be notified to the adjudicator to check for any conflict of interest. In the absence of any conflicts of interest, the Chairman in his absolute discretion will appoint the Assessors.

Submission of the redacted decision

The assessment will be conducted on the basis of:

- 2 redacted reasoned decisions made by him in adjudications conducted in the previous 2 years (the "Decisions"); and

- the accompanying procedural directions given by the adjudicator in the course of the 2 adjudications in a) above (the "Directions").

In order to facilitate comprehension by the Assessors (whilst preserving anonymity), it is preferable for the Decisions and the Directions to be redacted by the substitution of fictitious names/locations, rather than by simply blanking out the original text. We prefer that Adjudicators take care doing this and not simply cross out in biro!

The adjudicator must submit the Decisions and the Directions made preferably with cover emails to the Assessors. No further documents used in the adjudication should be submitted. The Assessors and TeCSA undertake not to disclose any details of the Decisions or the Directions to any third party.

It is not the role of the Assessors to review the merits of the Decisions. TeCSA is looking to ensure that decisions and procedural directions are presented in a professional, logical and understandable manner. The assessment criteria to be followed in reviewing the Decisions are set out in the Adjudication Service.

Procedure where no adjudications in the last 2 years

If the adjudicator has not conducted two adjudications within the previous two years he or she will be asked to explain why, with reasons, and submit two decisions and the accompanying procedural directions made within the previous five years. In the unlikely event that he has not conducted any such adjudications, he will again be asked to explain why, with reasons. Following their review of the reasons given by the adjudicator, the Assessors will:

Either

Agree that 2 decisions and the accompanying procedural directions made otherwise than within the previous 5 years shall constitute the Decisions and the Directions for the purposes of this TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Procedure;

Or

Recommend to the Chairman that the adjudicator's performance overall in the review shall be deemed to be "Not satisfactory" and that the adjudicator's name should be removed from the Adjudicator List.

The Chairman will consider any recommendation made above. Provided he is satisfied with the recommendation, the Chairman will decide to adopt the recommendation and inform the adjudicator accordingly. It is not unusual for some additional feedback to be supplied.

Should TeCSA decide to remove the name of an adjudicator from the Adjudicator List he will be so informed as soon as possible.

The Interview

Following their initial assessment of the Decisions and the Directions, the Assessors will arrange an interview with the Adjudicator lasting about a 1 hour. The Assessors will prepare for this as much as the Adjudicator! The Chairman will provide to the Assessors in advance of the interview a history of any upheld TeCSA complaints, judicial criticisms known to TeCSA (adjudicators remember the TeCSA declaration!) and any feedback received by TeCSA from the parties to any adjudication following an appointment, about the adjudicator over the period since the last review or entry onto the Adjudicator List, as appropriate. As explained above an adjudicator who is the subject of any adverse criticism shall be given an opportunity to comment on the information provided to the Assessors.

At the interview, the Assessors will raise points arising from their review of the Decisions and the Directions and any other matters that will enable them to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Adjudicator for the purpose of the assessment.

The criteria to be considered during the interview process are set out in the Adjudication Service. Should they consider it necessary or desirable to do so, the Assessors may require the adjudicator to provide further information.

On completion of the interview the Assessors will complete and forward to the Chairman of TeCSA an Adjudicator Assessment Report, to be signed by both Assessors, as shown in the Adjudication Service. The Assessors will recommend as to whether the adjudicator's overall performance, including during the interview and the drafting of the Decisions and the Directions, is:

- "Satisfactory";

- "Not Satisfactory" but the Assessors recommend remedial action which may enable the adjudicator to remain on the Adjudicator List. Such remedial action may include attending further training, submission of a written decision on a Case Study, undertaking pupillage or taking some other remedial action (requiring evidence of such) during a temporary period of suspension from the Adjudicator List;

- “Not Satisfactory” and the Assessors recommend that the adjudicator's name be removed from the Adjudicator List.

The Chairman will consider any recommendation made under paragraph 2.13 above. Provided he is satisfied with the recommendation, the Chairman will decide to confirm the recommendation and will inform the adjudicator accordingly.

Should TeCSA decide to remove the name of an adjudicator from the Adjudicator List he will be so informed as soon as possible.

All assessments remain strictly confidential to the adjudicator, the Assessors and TeCSA. Assessments will not be available to any other person or body.

Closing remarks

Adjudication has developed very closely to fast track arbitration in the twenty years I have followed and worked in it. It is still fast but more formal than it once was. Judges expect more, the public expects more and TeCSA expect more. 30 or more years ago arbitration moved closer to litigation and become less of an alternative to it, and with that arbitration all but died domestically.

Ironically, for many, adjudication is simply that which arbitration should have been since it is industry focused, it is pragmatic, it has strict time limits, it is (relatively) inexpensive and, importantly, it keeps projects moving.

Adjudication is alive and kicking because it largely fills a need. Long may it. The procedure and timetable may vary, but the parties are still looking to you the Adjudicator to resolve the dispute, which will involve identifying the issues, weighing the evidence, deciding who wins what points and producing a legally robust reasoned decision. In my view the analytical skills requisite to determine the dispute will never leave us unless artificial intelligence becomes a game changer in this field.

There will always be a need for the Adjudicator to be as straight as a bat and a person with an affinity with the subject matter ideally learned as much from the university of life as the classroom.

7 November 2017

Simon Tolson

Fenwick Elliott LLP

Appendix 1

TeCSA Adjudicator Undertaking

I acknowledge that I have been assessed by TeCSA as suitable to receive appointments made by the Chairman. I shall:

- Ensure that I or my firm maintain the necessary and appropriate professional indemnity insurance cover for my work. I confirm I will not accept appointments or undertake such work if I do not have such cover.

- Respond in good time to the Chairman when offered appointments. I recognise that if I take longer to respond than required by the relevant contract, or a time stated by the Chairman in his invitation, whichever is the shortest, the Chairman may offer the appointment to another person without contacting me. I also recognise the need to perform any duties in relation to disputes within appropriate timescales.

- Have appropriate methods of email communication available for all communication with TeCSA. I will normally use email to communicate with TeCSA unless the system is temporarily out of use at either end.

- Conduct the Adjudication in accordance with whatever rules are applicable under the relevant contract.

- Promptly provide any feedback in relation to an adjudication case history at the request of the Chairman.

- Comply with TeCSA's Adjudication Assessment Procedure from time to time notified to me.

- Keep TeCSA informed about any changes to the geographical and sectoral areas of my skills/work for future appointments and keep my CV up to date.

- Disclose any conflict of interest in relation to any proposed appointment. I shall also disclose any matter affecting any special requirement indicated in details provided by TeCSA, details of any other past or existing appointments, or issues that I know may arise during my appointment or in the future, which might have an impact on the appointment.

- Ensure that my fees shall not exceed the rate of £1,750 per day plus expenses and VAT and shall not require any advance payment of or security for my fees.

- I recognise I have a duty to uphold the appropriate professional and personal standards appropriate to enable the Chairman from time to time to have confidence in making appointments.

- I recognise I must notify TeCSA of any occasion where I have been the subject of judicial comments/criticism. I also undertake to co-operate with any complaints procedures TeCSA puts in place from time.

- I recognise that membership of the TeCSA List of Adjudicators does not guarantee a quota of (or any) appointments.

In signing and returning this document, I confirm my ongoing commitment to all of these matters without the need to make further declarations to TeCSA other than when requested specifically by TeCSA to do so.

Signed : …………………………………………….

Date : ……………………………………………….

- 1. Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (as amended by the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009).

- 2. [2014] EWHC 3710 (TCC).

- 3. [2016] 2 All ER (Comm) 129 : [2016] BLR 187.

- 4. Davidson v Scottish Ministers [2004] UKHL 34.

- 5. Would an informed and fair-minded observer, with knowledge of all the relevant circumstances, conclude that there was a real possibility that the tribunal was biased?

The test is objective and not dependant on the characteristics of the parties.

The Court must look at all the facts available to it – material circumstances will include any explanation given by the decision maker under review –

Fair - minded observer must:

* Know all relevant publically available facts;

* Neither complacent nor unduly sensitive or suspicious;

* Must be assumed to be “fairly perspicacious”! - 6. [2016] EWHC 2283 (TCC).

- 7. [2016] EWHC 2283 (TCC).

- 8. [2015] EWHC 661 (TCC).

- 9. TeCSA Rules (Rule 13) expressly require fairness and impartiality and prohibit acting if a conflict (Rule 20-4).

- 10. The panel has been multi-disciplinary since its initial course in 1996 to TeCSA Solicitors. TECBAR also makes appointments, but in much smaller numbers, because barrister adjudicators are often chosen directly by well-informed parties or their advisers

- 11. Last updated in May 2014 but due to be updated later in November 2017.

- 12. Reminder of minimum requirements:

• Stage 1: Assessment of (redacted) decisions;

* Stage 2: The Interview: ‘satisfactory’ or ‘not satisfactory’;

* Ad-hoc assessments if serious complaint received or judicial criticism;

* Interviews conducted.

Each adjudicator on the Adjudicator List shall:

(a) Give the undertaking in the form at Error! Reference source not found. (to the Adjudication Service as amended from time to time) (the "TeCSA Adjudicator Undertaking”);

(b) Undertake the Continuing Professional Development required by TeCSA from time to time. TeCSA’s current requirements are set out in Error! Reference source not found. (the "Requirements for TeCSA Adjudicators' Continuing Professional Development ("CPD")”);

(c) Be regularly and independently assessed in accordance with the requirements of TeCSA from time to time. TeCSA’s current requirements are set out in Error! Reference source not found. (the "TeCSA Adjudicator Assessment Procedure”). - 13. Carter v Nuttall [April 2002] HH Judge Bowsher QC: “It was accepted before me that the jurisdiction of an adjudicator derives, at least in a case like the present, from the Notice of Adjudication. Put simply, the adjudicator has jurisdiction to decide a “dispute” which is the subject of a Notice of Adjudication, but he has no jurisdiction to decide something, which is not covered by the relevant Notice of Adjudication. It seems to me that what is or is not the subject of a Notice of Adjudication depends upon proper construction of the relevant notice…”

- 14. The Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998, SI 1998/649; The Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998 (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2011, SI 2011/2333.

- 15. grievance PROCEDURE: If an Adjudicator is dissatisfied with any decision made by TeCSA or any representative of TeCSA then it shall be dealt with subject to and in accordance with the Grievance Procedure incorporated in Error! Reference source not found. (the "TeCSA Adjudicator Grievance Procedure") of the Adjudication Service.

- 16. Those of you here that are members of the Adjudication Society and/or the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators may well have seen their joint third update of a guidance note for adjudicators, Jurisdiction of the UK Construction Adjudicator, published 1 January 2016: http://www.ciarb.org/docs/default-source/ciarbdocuments/construction-adj... [3].

- 17. Where the need for the ‘right’ answer has been subordinated by the need to have an answer quickly” (see Carillion v Devonport Royal Dockyard [2006] BLR 150).

- 18. One question all adjudicators should address immediately on receiving the referral notice is whether they have been appointed in accordance with the contract and/or the Scheme for Construction Contracts. This normally only takes a few minutes and can save the parties considerable time and money if it is raised at the outset of an adjudication. We have seen from cases such as Twintec Ltd v Volkerfitzpatrick Ltd [2014] EWHC 10 (TCC) that if an adjudicator’s appointment is made under the wrong set of adjudication provisions then it will be invalid and the adjudicator’s decision will not be enforceable. This being one of those rare and exceptional circumstances when a court should intervene to stop an adjudication from continuing as it would not be “just and reasonable” to permit an adjudication to continue in circumstances where the resulting decision would be unenforceable.

- 19. Consider “balance of convenience” in stopping.

- 20. Rule 12 of the rules gives the adjudicator the power to decide his own substantive jurisdiction. Without such a provision, which is still fairly unusual, the adjudicator would not be empowered to make a binding decision in this regard. What normally happens in such circumstances is that the jurisdiction issue is simply held over until after the adjudicator has reached his decision and the successful party seeks to enforce his substantive decision through summary court proceedings. A decision by the adjudicator upon his own jurisdiction cannot be re-opened by the losing party in the context of summary enforcement proceedings save in the most exceptional circumstances.

- 21. 2 AC 357, HL.

- 22. Under the Act, as amended by the 2009 Act, there is now a requirement that a construction contract must include a provision in writing permitting the adjudicator to correct a decision so as to remove a clerical or typographical error arising by accident or omission. Unlike the provision in s.57 of the Arbitration Act 1996 giving an arbitrator the power to correct a mistake in an award, s.108(3A) requires no detail on the way in which the power to correct an adjudicator's decision should operate. If the parties do not incorporate such a provision then the Scheme, as amended, applies and this provides more detail and states that the adjudicator may correct a decision either on the adjudicator's own initiative or on the application of a party; that any correction of a decision must be made within five days of the delivery of the decision to the parties; that, as soon as possible after correcting a decision, the adjudicator must deliver a copy of the corrected decision to each of the parties to the contract; and that any correction of a decision forms part of the decision.

- 23. In those early days the emphasis or model some followed was that the adjudicator was brought in to make an independent re-cap of an engineer’s decision or an architect’s certificate or QS valuation and as between contractor and subcontractor the adjudicator was merely an outside independent QS/architect/engineer/consultant making a quasi-certificate (a Decision). So the process or procedure was only as “formal” as the industry expected from any certifier. In other words for some the adjudicator was an even handed person from construction who was a busy QS/engineer/architect/consultant with a side line of adjudicating when invited. Quite how this person adjudicated was for some not in point at all. He just got stuck-in! Those were the Wild West days of 1998 to about 2002, it was refreshing, even exciting, but could not last.

- 24. At an Arbitration and Adjudication seminar held at the University of London's Queen Mary and Westfield College in May 1996 under the chairmanship of the Rt. Hon. Lord Justice Saville (as he then was), other speakers-including Professors Goode, Q.C., John Adams, Stewart Boyd, Q.C., Bruce Harris and Toby Landau. Lord Justice Saville suggested that adjudication sounded much like a Mareva injunction in that it could provide a "cheap and dirty" solution based on information, which, in the ultimate analysis, may prove inaccurate. In the meantime, the party at the wrong end of the decision or injunction has been ruined. Philip Capper replied that it was what the customers wanted: architects and engineers had been doing something similar for decades…! The "pay now argue later" approach, which Lord Ackner describes, has in my opinion been overtaken. Adjudication is now a mainstream post-contractual method of dispute resolution. And, for all the obvious reasons, it is a mighty attractive choice for claimants.

- 25. Impartiality is the embodiment of fairness and a paramount consideration. It is not the same thing as independence, but the rules of natural justice embrace the latter.

- 26. The Court of Appeal has warned judges not to ‘cut and paste’ their rulings from submissions made by one party to a case, with Lord Justice Underhill saying it was “thoroughly bad practice”. The appeal in Crinion & Anor v IG Markets Ltd [2013] EWCA Civ 587 was founded purely on the fact that HHJ Simon Brown QC in Birmingham Mercantile Court had used the closing submission from the claimant’s counsel, Stewart Chirnside, as the basis for his ruling. 94% of the words of the judgment represented Mr counsel’s drafting. It said this created the impression that the judge had abdicated his core judicial responsibility to think through for himself the issues which it was his job to decide, and that he had simply slavishly adopted Mr Chirnside’s arguments as his own.