June 2022

NEC Accepted Programmes: A Practical Guide

By Claire King1

The Accepted Programme sits right at the heart of the NEC form of contract. Its aim is to encourage good project management by not only ensuring that all parties to the project know what they have to do and when, but also by facilitating the prompt and prospective assessment of compensation events as and when they occur on the project. In order to achieve these aims, numerous prescriptive procedures governing Accepted Programmes are provided for.

All too often, however, these procedures break down, sometimes right from the beginning of the project. This can be for a wide variety of reasons, but all too often it is because parties do not fully understand what an Accepted Programme should contain or the processes for updating it.

In this Insight, we set out a practical guide to all things related to NEC Accepted Programmes, focusing on the NEC4 Engineering and Construction Contract form (the “NEC4”). In particular, we examine:

- How the Accepted Programme fits into the NEC4 as a whole;

- What the requirements for an Accepted Programme are;

- The processes for agreeing an Accepted Programme;

- How parties can keep the processes for updating and agreeing the Accepted Programme going through the lifespan of a project; and, finally

- How can the disputes and game playing seen all too often in relation to Accepted Programmes be avoided and/or their consequences mitigated?

NEC Objectives and the role of the Accepted Programme

The NEC’s objectives are to “facilitate and encourage good management of risks and uncertainties, using clear and simple language”.2 To achieve that goal, the NEC encourages the early identification of problems and a proactive approach to addressing those problems. The idea is firmly that issues are resolved as work progresses so that there is no final account process (or associated dispute) at the end of the job. These goals are supported by prescriptive contractual procedures. All parties also have a duty to act in a “spirit of mutual trust and cooperation”.3

The Accepted Programme is a key project management tool in the NEC form and is crucial for achieving the NEC’s objectives. Broadly, it has two roles:

- To ensure that all parties know what they have to do, and when; and

- To provide a tool to enable the prompt and (hopefully) prospective assessment of compensation events and, specifically, the extensions of time claimed pursuant to them.

A tool for assessing compensation events contemporaneously

The Accepted Programme is intended to encourage collaborative working and dispute avoidance. In particular, it provides a tool to allow the assessment of extensions of time (via compensation events) contemporaneously, and without the need for a complex and expensive delay analysis.

Under clause 63.5, the Accepted Programme is the tool the Project Manager should use for assessing compensation events.4 The Accepted Programme used for assessing an extension of time (compensation event) is the one current at the dividing date. The dividing date is set out in clause 63.1:

“For a compensation event that arises from the Project Manager or the Supervisor giving an instruction or notification, issuing the certificate or changing an earlier decision, the dividing date is the date of that communication.

For other compensation events, the dividing date is the date of the notification of the compensation event.” [Emphasis added]

Sometimes amendments are made to the definition of the dividing date. For example, stating that the dividing date is the date a quotation is requested. In the author’s view, this is to be discouraged. The logic of the dividing date in the definitions is that this is as close as possible to when the event itself occurred (assuming there is prompt notification of a compensation event). If the date is anything else, assessment can become much more difficult and theoretical (i.e. removed from the reality of what is happening on the ground), thus building in more room for unnecessary disputes.

Obviously, the closer the Accepted Programme is prepared to the dividing date, the easier it should be for the Project Manager to assess the impact of any compensation event (and for a Contractor to update the Accepted Programme to show the impact of any compensation event).

A hook for compensation events

Incorporating crucial dates into the Accepted Programme is encouraged by the fact that there are a number of specific compensation events which cross reference to the Accepted Programme. These include:

- Clause 60.1 (2): Failure to allow access by the date shown in the Accepted Programme;

- Clause 60.1 (3): The Client does not provide something by the date shown in the Accepted Programme; and

- Clause 60.1 (5): The Client or others do not work within the times shown on the Accepted Programme.

Clause 60.1 (19), the NEC equivalent to a force majeure provision, also expressly cross references to the Accepted Programme and, more specifically, the date shown for planned Completion shown in the Accepted Programme, as part of the test as to whether there is a compensation event or not. Obviously, in order to claim these compensation events, the Accepted Programme must have been prepared properly and contain the relevant dates as hooks for any claim.

Carrots and sticks to encourage the production of an Accepted Programme

Given the central importance of the Accepted Programme, the NEC4 also contains both carrots and sticks to encourage their production and updating. Clause 50.5, for example, provides that if there is no programme in the Contract Data, one quarter of the Price of Work Done to Date is retained in assessments of the amount due until the Contractor has submitted a first programme (showing the information which the contract requires) to the Project Manager for acceptance.

Clauses 64.1 and 60.2 also provide a strong incentive for the contractor to submit their programmes. If the Contractor does not do so, they lose control of the compensation event assessment process. First of all, the Project Manager is required to assess all compensation events5 and, secondly, the Project Manager should use their own assessment of what the programme should be to assess the impact of the compensation event.6

Setting up an Accepted Programme

Section 3 of the NEC4 contains all of the key provisions governing what the first Accepted Programme is and what it should contain.

The first Accepted Programme is either the programme identified in the Contract Data or the programme to be submitted to the Project Manager for acceptance.7 It is important to note that the Accepted Programme and the Activity Schedule (for Options A or C) are not the same documents but are required to be correlated. Clause 31.4 (Option A) requires that “the Contractor provides information which shows how each activity on the Activity Schedule relates to the operations on each programme submitted for acceptance”. This is an ongoing duty and doesn’t just relate to the first Accepted Programme.

What must an Accepted Programme contain?

Assuming the first Accepted Programme is not already attached to the contract, then the contractor needs to note the very detailed and prescriptive information listed in clause 31.2. This includes:

- The starting date, access dates, Key Dates and Completion Date;

- Planned Completion;

- The order and timing of the operations which the Contractor plans to do in order to Provide the Works;

- The order and timing of work of the Client and Others as last agreed with them by the Contractor, or if not so agreed, as stated in the Scope;

- The dates when the Contractor plans to meet each Condition stated for the Key Dates and to complete other work needed to allow the Client and Others to do their work;

- Provision for float, time risk allowances, health and safety requirements, and the procedures set out in the Contract;

- The dates when the Contractor will need: access to a part of the Site if later than its access date, acceptances, Plant and Materials and other things to be provided by the Client, and information from Others;

- For each operation, a statement of how the Contractor plans to do the work identifying the principal Equipment and other resources which will be used; and

- Other information which the Scope requires.

In relation to the last point, there may be other information which the Scope requires the Accepted Programme to contain which is sometimes not obvious (for example, because it is buried deep in the Works Information). As such, a comprehensive review of all the information attached to the contract needs to be undertaken to ensure the Accepted Programme is compliant.

An example of a programme showing key information is set out below (Figure 1):

Figure 1 – Key Information

Statement of how the Contractor plans to do the work

Along with each Accepted Programme, there is also a requirement for a statement of how the Contractor plans to do the work (sometimes called a programme narrative).8 This should include details of the:

- Sequence of planned works;

- Resources required (types and numbers);

- Key equipment required;

- Critical path;

- Time risk allowances, assumptions used;

- Key dates such as access dates or information from others; and

- Description of working calendars and interfaces.

This is an important document and should be issued with every programme submitted for acceptance. Practically, it provides the Project Manager with visibility of what the programme is really showing. It also shows what has changed, and why, since the last Accepted Programme. As such, it is a vital project tool and, when done well, can help to prevent a breakdown of the Accepted Programme process.

Time risk allowance v float

Two concepts that are often confused are the concept of float within the NEC programme and time risk allowance (known as “TRA”). These are different concepts, and it is important to understand them in order to ensure that they are used correctly.

Float is found in all programmes. In its simplest form, it is a gap between the activities that allows them to be delayed without causing critical delay to the end date of the programme. However, terminal float is specifically identified in the NEC (as opposed to other contract forms) as being “owned” by the Contractor. This is important because, if there is a compensation event that impacts on the critical path and is at the Employer’s risk, the Contractor will keep the benefit of the terminal float.9 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2 - Float

On the other hand, TRA is a specific identified risk added into the programme. It needs to be identified and explained and can be shown as separate activities in the programme or integrated within the planned activity duration. However, the key is that it needs to be identified so all parties can understand what is in the programme and how it should be used. This “open” or “collaborative” approach ensures that all parties buy into the programme and will use it as a good project management tool and believe it for the purposes of assessing compensation events. Examples of how TRA can be shown in the programme are in the image (Figure 3) below:

Figure 3 – Time Risk Allowance (“TRA”)

We would encourage parties to be open about where TRA is in the programme rather than hiding it. Blocked durations (shown clearly) are probably the easiest “open” method to adopt in practise.

Reviewing the Accepted Programme

Once the Accepted Programme has been submitted, the Project Manager has two weeks to notify his acceptance or reasons for rejecting it. The reasons for rejecting the programme are limited to the following:

- The Contractor’s plans are not practicable;

- It does not show the information required by the Contract;

- It does not represent the Contractor’s plans realistically; or

- It does not comply with the Scope.10

When considering assessing the Accepted Programme, the Project Manager should act as they do when they are a certifier, i.e., impartially and take their duties under Clause 10 seriously.11

What happens if the Project Manager does not respond?

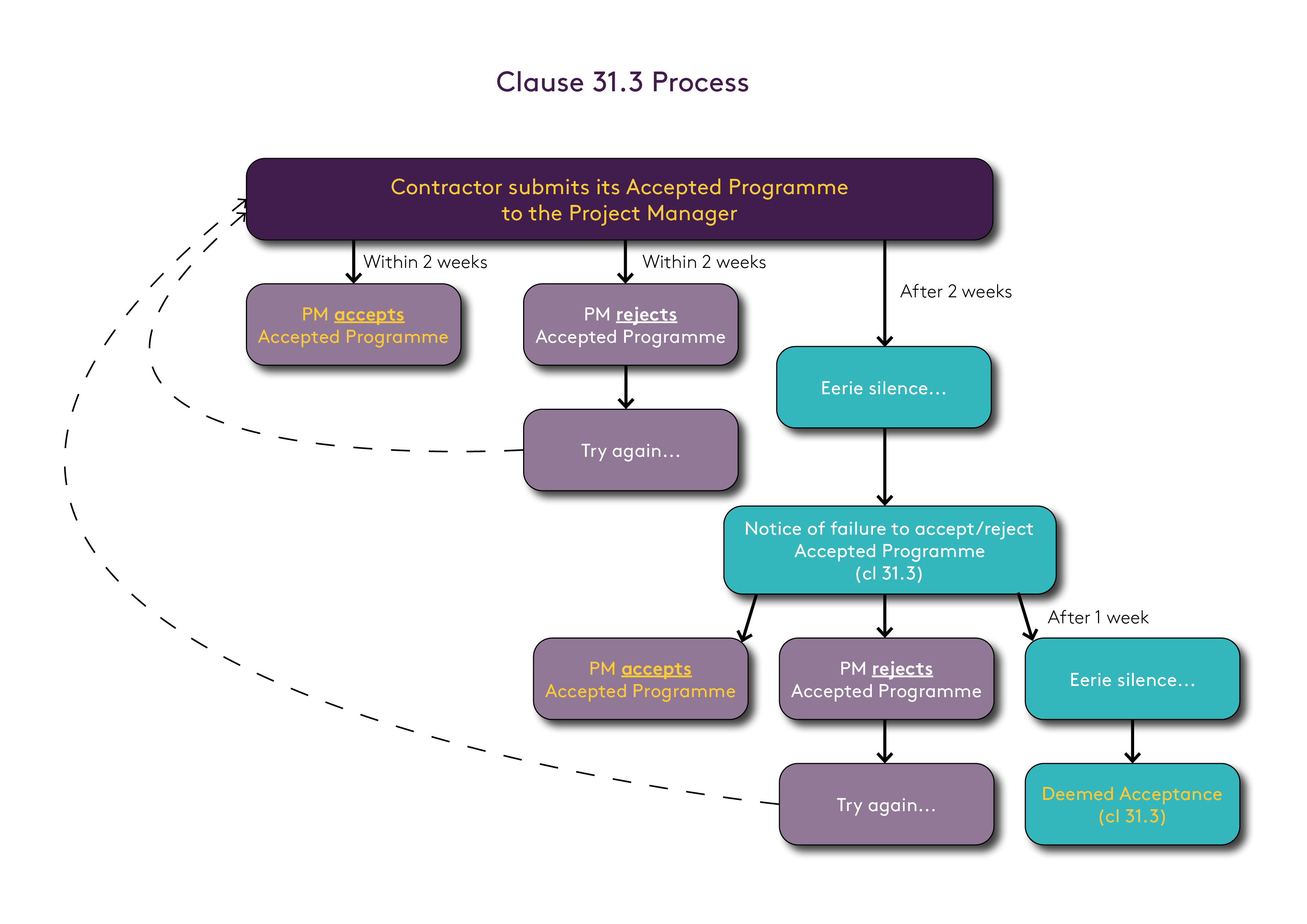

If the Project Manager does not respond within two weeks, then there is a useful deeming provision provided within the NEC4 which, unfortunately, is not present in the NEC3. After two weeks, the Contractor can submit a notice of failure to accept or reject the Accepted Programme under clause 31.3. If the Project Manager remains silent after 1 week, then there is deemed acceptance of the programme.

A flow chart showing the procedure for accepting the Accepted Programme is set out below (Figure 4) and applies to each revision as well.

Figure 4 – Clause 31.3 Process – The Accepted Programme

This is a very useful tool to have where a Project Manager is perhaps too slow to review programmes when submitted. Use it! If the process gets behind (especially where there are lots of subcontractors also flowing their Accepted Programmes into the main contractor’s programmes), this can be a recipe for disputes further down the line as it becomes more and more difficult to get an agreed Accepted Programme.

My first Accepted Programme has been accepted: what next?

The NEC4 also provides for Accepted Programmes to be submitted within the periods laid down in the Contract Data. It is important this period is realistic. If there are multiple subcontractors involved, they also need to feed into the process and this process can take time. This time period is, therefore, something to think about carefully. Too often and it becomes an administrative burden that means the whole process may break down; too infrequently and the Accepted Programme becomes a tool that is not as useful as it could be for assessing compensation events or getting people to buy into it as a genuine project management tool.

What should I show in my updates?

Pursuant to clause 32.1, each revised programme must show:

- The actual progress it achieved on each operation and its effect upon the time of the remaining work;

- How the Contractor plans to deal with any delays to correct and notify Defects; and

- Any other changes which the Contractor proposes to make to the Accepted Programme.

There is no mechanism for the client to instruct a programme. The process is contractor-led. Ideally, a full update needs to be provided so the programme is seen as reliable and a genuine tool for the project to use and rely on. This means showing any anticipated changes, delays or subcontractor issues. If the updated programme isn’t open about problems faced by the job, the whole process gradually breaks down.

Ensuring that the update and progress records are comprehensive will also help with the approval process. Equally, if the planning statement is updated, explain what has changed, and why, since the last Accepted Programme. This should help with the approval process.

Finally, a statement can also explain how any TRA has been drawn down on, or any changes made to the TRA, in the update period. It is often tempting to hold on to the TRA for a “rainy day”, but best practice is to release the TRA if it hasn’t been used but was associated with an item that has now occurred. This will again encourage people to believe in the programme and see it as a genuine tool for project management. Equally, if there are new events that need TRA (for example, Covid 19), then these should be added in.

How do I deal with delays to the project?

Where you need to submit a quotation for a compensation event, this should include the assessment of (prospective) delay impact by the Contractor. As set out above, it is important to get the dividing date right and also to use the Accepted Programme that was “current at the dividing date”.12

Time impact is usually shown on the programme by adding new activities to model the delay event which will include new or extra TRA if appropriate. An example of how to show such a delay is set out below (Figure 5):

Figure 5 – Time impact

Common Problems

Unfortunately, too often we see issues building up right from the beginning of the project. For example, these problems include, but are in no way limited to:

1. Delays to the submission of the initial Accepted Programme meaning you are constantly trying to catch up and nobody can use the Accepted Programme as a project tool in the way intended;

2. Subcontractors providing Accepted Programmes which are not realistic and, therefore, extremely difficulty to feed into the main contractor’s programme. This can be for a variety of reasons including the subcontractors’ own failure or lack of resources perhaps. However, equally, subcontractors quite often have to work from an incomplete picture provided by a main contractor and, accordingly, are shooting at an invisible target. Providing the necessary level of information to allow a subcontractor to properly programme their works is essential. Often, there is a circular process required with information exchanged on an interactive basis before the optimum level is reached;

3. While not catastrophic, working on different programming software can cause very real difficulties and make the timetable for flowing up a subcontractor’s Accepted Programme into the main contractor’s Accepted Programme more difficult;

4. Quite often subcontractors are working on different contract forms meaning they have no obligation to provide regular updates, or if they do, they are in a slightly different format to that required by the NEC. This is something to avoid if at possible. Equally, if subcontractors are unfamiliar with the NEC form, they will need an education process so that they understand what is required from them;

5. Constant rejection by Project Managers is not unheard of. Quite often this is because there is one issue in the original, or an early, Accepted Programme which is never quite resolved because the relevant people don’t sit around the table to discuss it and understand the thought processes which underpin it. This initial rejection can be for a sensible reason but quite often snowballs as the Accepted Programme gets further and further behind the work being carried out on the project on the ground;

6. Occasionally, we also see deliberate rejection of Accepted Programmes by Project Managers (or contractors in relation to subcontractor programmes) so that they can assess the compensation events. This is not conduct we would recommend, not least because it leads to problems down the line and serves to harden people’s attitudes meaning that the collaborative ‘working together’ ethos of the NEC can be fatally undermined;13

7. Other issues include failure to show key information (such as dates when the client was to provide information or access to various parts of the site) on the Accepted Programme meaning there is no entitlement to compensation events. What should be an easy hit for a contractor or subcontractor then gives no entitlement; and

8. Accepted Programmes are submitted but don’t show the potential impact of compensation events, which are disputed or not accepted at that time, “just in case”. This then makes assessing them very difficult for all involved.

How can I get around these problems?

It is, of course, much easier to list the problems than to find solutions to them. However, practical advice to resolve these issues includes:

1. Sticking to the contractual deadlines right from the start. This means sufficient programming resource needs to be allocated. Getting the Accepted Programme right needs to be prioritised and put higher up the list of things to do. Main contractors need to get around the table with their subcontractors to discuss any issues and ensure the subcontractors can provide the information the main contractor needs to feed up the line;

2. Getting around the table and explaining what you’ve done (helped by a detailed programming statement) is also essential if issues are starting to build up. It may be that it is just not clear what the Accepted Programme is showing and why, but that once explained the problem can be resolved;

3. If problems continue and Accepted Programmes continue to be rejected (for what you consider to be invalid reasons), then it is even more important to continue the process. Continue to submit accurate updated programmes. They will save you both time and money if there is a dispute at the end of the project, and they are good contemporaneous evidence of delays if they are accurate. They are also intended to be a project management tool and, sticking to that, discipline should hopefully encourage good project management even when others are failing to perform their role;

4. Don’t forget the Clause 31.3 notification process set out in the flow diagram above. That may be a way of getting deemed acceptance under the NEC 4 programme (it does not apply to the NEC 3 form) if a Project Manager is being particularly slow; and

5. Finally, it may be worth thinking about escalating the issue of the Accepted Programme further up the command chain. Getting an Accepted Programme agreed at the beginning of the job is important and if this is proving very difficult then it can be a recipe for problems later on in the project. Clause W2 of the NEC4 provides for escalation to senior representatives, and parties should not be afraid to use this tool if necessary. One other tactic to consider (albeit an aggressive one) is to adjudicate and ask for a declaration that a programme should be accepted. This would undoubtedly be a bold step to take, particularly at the start of a project, and it may damage relationships going forwards. That said, if the Accepted Programme submitted is being rejected for minor or inconsequential issues (or, indeed, just so the Project Manger can assess compensation events), then this is the sort of behaviour that may be worth considering nipping in the bud. Otherwise, problems can rapidly snowball, and this is a recipe for a final account dispute down the line.

Past the point of no return?

All too often, we see classic final account disputes at the end of NEC projects which involve substantial extension of time claims that were not resolved prospectively. Questions as to what form of delay analysis is required to support any claim then come to the fore.

Common debates include whether there should be a prospective or retrospective analysis. The Northern Ireland Housing Executive vs Healthy Buildings (Ireland) Limited case14 provides some guidance in relation to this and suggests that a retrospective analysis is acceptable. This is despite the fact that the Contract itself arguably provides for a prospective analysis. As Deeny J stated:

“Why should I shut my eyes and grope in the dark when the material is available to show what work they actually did and how much it cost them?”15

From a delay analyst’s perspective, there are a number of possible approaches that could be adopted. For example, it might be possible to undertake a compliant time impact analysis stepping through each compensation event in divide and date order based on the most appropriate baseline programme at that time. However, as the impact of a compensation event at the end of a project is likely to be known, that may not be the best way to analyse the delay. In particular, it may produce theoretical results which do not reflect what actually happened on the project.

The middle ground is doing a sense check to see if the results of your time impact analysis are close to what actually happened or carrying out a more fact-based analysis of delays (which would be supported by the Northern Ireland Housing Executive case) can be undertaken with a time slice window analysis. However, that may be less attractive to NEC purists despite Northern Ireland Housing Executive suggesting that it should be acceptable. Belt and braces would obviously be the best approach (i.e., a perspective and retrospective fact-based analysis), but that takes time and cost to prepare.

Obviously, if the delay analysis you produce is entirely theoretical and does not accord with the contemporaneous emails and progress records generally, it is going to be easy to undermine in an adjudication. Accordingly, it is important to check that the progress data available supports the analysis produced to ensure you don’t have an entirely theoretical result.

Overview

Unfortunately, carrying out a delay analysis at the end of the job will take time and can be expensive. Furthermore, memories are not as fresh, staff leave, and records are lost, meaning that being in this position is always unattractive. For this reason, it is incumbent on all parties involved in NEC projects to try to understand, and fully buy into, the Accepted Programme process. In particular, to resolve issues as and when they occur so that they don’t snowball. This is much easier if the programmes are accurate (both in terms of as-built data and logic) and supported by a detailed narrative explaining the thinking that lies behind it, and a transparent approach to showing delays and TRA is adopted.

- 1. By Claire King. With thanks to Scott Jardine of Ankura for his excellent graphics. These were first used in the Fenwick Elliott webinar [1] by Claire King, Mark Pantry and Scott Jardine on the same topic held on 19 May 2022.

- 2. See the preface to NEC 4 Engineering and Construction Contract dated June 2017.

- 3. See Clause 10.2 which provides: “The Parties, the Project Manager and the Supervisor act in a spirit of mutual trust and cooperation.”

- 4. Clause 63.5 of the NEC 4 provides: “a delay to the Completion Date is assessed as the length of time that, due to the compensation event, planned Completion is later than planned Completion as shown on the Accepted Programme current at the dividing date…. When assessing delay only those operations that the Contractor has not completed and which are affected where the compensation event are changed”.

- 5. See bullets 3 and 4 of clause 64.1.

- 6. Clause 64.2 provides that: “the Project Manager assesses the programme for the remaining work and uses it in the assessment of a compensation event if (1) there is no Accepted Programme, (2) the Contractor has not submitted a programme or alterations to a programme for acceptance as required by the Contract; or (3) the Project Manager has not accepted the Contractor’s latest programme for one of the reasons stated in the Contract”.

- 7. See Clause 31.1.

- 8. See Clause 31.2.

- 9. See Clause 63.5.

- 10. See Clause 31.3.

- 11. See Scheldebouw BV v St James Homes (Grosvenor Dock) Limited [2006] EWHC 89 (TCC).

- 12. See Clause 63.5.

- 13. See Clauses 10.1 and 10.2.

- 14. [2017] NIQB 43.

- 15. Emphasis added.